3

misconceptions can also surface in the middle of a lesson when we may not necessarily be

looking for them, and that’s okay too. If we know a

misconception exists in any part of a lesson

cycle, we can and should address it.

One way to detect a misconception is to listen to student discussions. If you hear something

suspicious, be inquisitive. Ask the student why or how, or say, “Tell me more.” Do this regardless

of whether a student is on the right track or not so that they become accustomed to explaining

their thinking. Determine whether students have a conceptual understanding or have simply

memorized or copied an answer or restated what someone else said. Also, equal opportunity

questioning keeps students from automatically assuming they are wrong when you question

them. Another way of truly understanding how s

tudents think is through their writing or

drawings. Provide open-ended questions as prompts. Allow an

ywhere from 3 to 15 minutes

for students to answer depending on the time available and the complexity of the question

or concept being addressed. Some students may find writing or drawing less threatening

than verbally explaining their thinking in front of the class. If students struggle with writing,

implement a quick think-pair-share activity to allow v

erbal processing in a safe setting

before writing explanations. You can further support their writing through the use of

sentence stems or sentence frames.

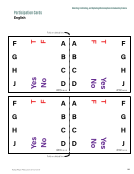

Various formative assessment strategies exist to detect misconceptions. You will see some

of these strategies used to detect the misconceptions addressed in this book. Templates for

creating your own activities to detect misconceptions can be found in the Appendix.

Confronting Misconceptions

Once we know t

hat a misconception exists, we have to provide an opportunity for students to

confront it. Confronting a misconception is much more difficult than detecting or replacing it

because we have to create cognitive dissonance, the mental discomfort that occurs when faced

with two conflicting ideas (Cherry 2022). Effective cognitive dissonance requires deep thinking

and often results in an uncomfortable encounter for the student and the teacher. The brain

seeks to make new inf

ormation fit within existing schema, or how t

hat person understands an

idea or concept. When new inf

ormation clashes with existing schema, the person is forced to

mentally struggle to make sense of the new inf

ormation. Changing incorrect thinking requires

reconfiguring brain pathways and replacing existing schema. This is a mentally exhausting task!

An established safe learning environment is critical for students to more readily engage in this

step because it can be unsettling to own and reconcile faulty thinking in front of one’s peers

and a teacher. Students are more likely to face their misconceptions when they are in an

open-minded, supportive physical and mental space.

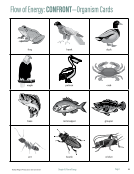

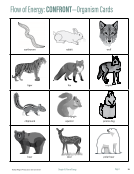

As with Detect, more than one way to confront misconceptions exists. If students built a model

or drew an

illustration for the Detect activity, an effective Confront activity would be asking

students to compare and study their models or drawings to a model, illustration, phenomenon,

or investigation that demonstrates the correct idea or concept. This could also be accomplished

misconceptions can also surface in the middle of a lesson when we may not necessarily be

looking for them, and that’s okay too. If we know a

misconception exists in any part of a lesson

cycle, we can and should address it.

One way to detect a misconception is to listen to student discussions. If you hear something

suspicious, be inquisitive. Ask the student why or how, or say, “Tell me more.” Do this regardless

of whether a student is on the right track or not so that they become accustomed to explaining

their thinking. Determine whether students have a conceptual understanding or have simply

memorized or copied an answer or restated what someone else said. Also, equal opportunity

questioning keeps students from automatically assuming they are wrong when you question

them. Another way of truly understanding how s

tudents think is through their writing or

drawings. Provide open-ended questions as prompts. Allow an

ywhere from 3 to 15 minutes

for students to answer depending on the time available and the complexity of the question

or concept being addressed. Some students may find writing or drawing less threatening

than verbally explaining their thinking in front of the class. If students struggle with writing,

implement a quick think-pair-share activity to allow v

erbal processing in a safe setting

before writing explanations. You can further support their writing through the use of

sentence stems or sentence frames.

Various formative assessment strategies exist to detect misconceptions. You will see some

of these strategies used to detect the misconceptions addressed in this book. Templates for

creating your own activities to detect misconceptions can be found in the Appendix.

Confronting Misconceptions

Once we know t

hat a misconception exists, we have to provide an opportunity for students to

confront it. Confronting a misconception is much more difficult than detecting or replacing it

because we have to create cognitive dissonance, the mental discomfort that occurs when faced

with two conflicting ideas (Cherry 2022). Effective cognitive dissonance requires deep thinking

and often results in an uncomfortable encounter for the student and the teacher. The brain

seeks to make new inf

ormation fit within existing schema, or how t

hat person understands an

idea or concept. When new inf

ormation clashes with existing schema, the person is forced to

mentally struggle to make sense of the new inf

ormation. Changing incorrect thinking requires

reconfiguring brain pathways and replacing existing schema. This is a mentally exhausting task!

An established safe learning environment is critical for students to more readily engage in this

step because it can be unsettling to own and reconcile faulty thinking in front of one’s peers

and a teacher. Students are more likely to face their misconceptions when they are in an

open-minded, supportive physical and mental space.

As with Detect, more than one way to confront misconceptions exists. If students built a model

or drew an

illustration for the Detect activity, an effective Confront activity would be asking

students to compare and study their models or drawings to a model, illustration, phenomenon,

or investigation that demonstrates the correct idea or concept. This could also be accomplished